Head to Head: The National Football League & Brain Injury

NYU Langone’s High School Bioethics Project developed this primer so students may understand the basics of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and tau protein, as well as trends in biomedical research involving CTE and the National Football League (NFL). It also allows students to explore ethical questions related to safety, risk, and health policy.

Curriculum Integration Ideas

This guide may be used in life sciences classes during units that cover topics including the following:

- sports and health

- anatomy, physiology, and neurology

- public policy discussions on safety, risk, and sports

Head Injuries in the NFL

Over the past few years, concussions suffered by NFL players have been in the news. Many high-profile football players—superstars like former Philadelphia Eagles running back Brian Westbrook and Washington Redskins running back Clinton Portis—have been sidelined by severe head injuries. Although severe head trauma and brain injury have gotten much attention in the media, efforts to minimize these injuries have lagged. The NFL has only recently begun taking steps to protect its players in response to a torrent of criticism.

Background on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and Tau Protein

In 2008, research surfaced that was gathered by neuropathologist Ann McKee, MD, from the Bedford VA Medical Center and CTE Center at Boston University Medical Center. After studying the brains of 12 former football players over a 2-year period, Dr. McKee found evidence of neurodegeneration. Each brain showed apparent signs of repeated trauma, the only cause of a condition known as CTE. CTE has been found to lead to depression, loss of judgment, inability to control impulse, rages, and memory loss, and can ultimately result in dementia. What’s worse, these symptoms are not immediately apparent and can emerge up to 10 years after one stops playing football.

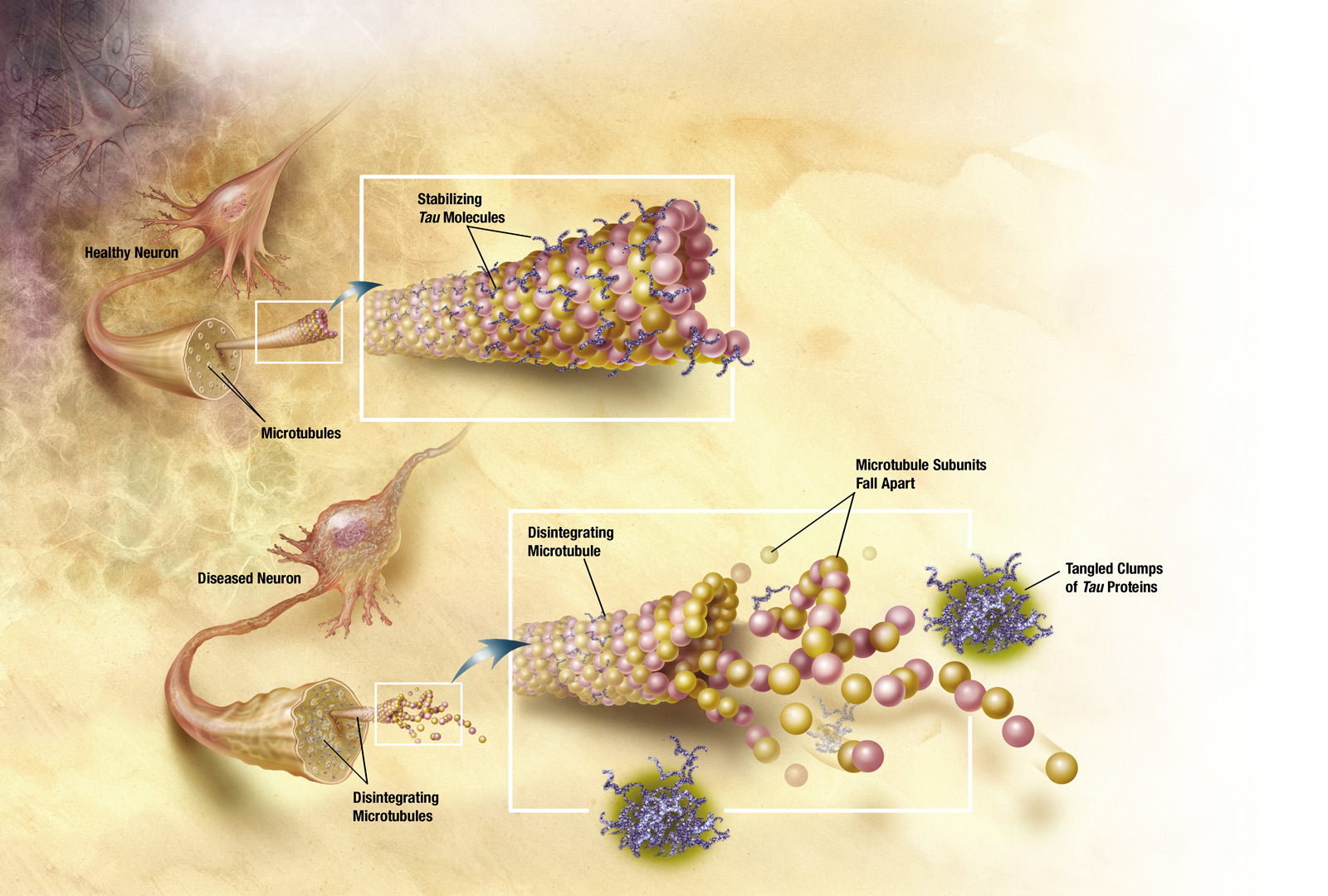

As Dr. McKee found, with every accumulation of brain trauma there is an increased effect on tau protein in the brain. Tau protein is a microtubule-associated protein (MAP) that plays a large role in microtubule stability. Microtubules transport nutrients and molecules within cells of the brain. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau is altered chemically and begins pairing with other tau threads, becoming tangled, and a similar thing happens in CTE. These altered tau structures collapse, causing microtubules to disintegrate and the cells to die.

This deterioration of tau protein appears in the brain as small black specks. In areas of the brain that have experienced repeated damage, entire sections can become stained or discolored, turning brown or black. In the case study of John Grimsley, a former NFL player who died at age 45 from an accidental gunshot wound, Dr. McKee displays the difference between the brain of a healthy person with no evidence of degeneration, a football player with obvious presence of degeneration, and a boxer with extreme levels of degeneration. In the cross-section slides (accessible halfway down the page, by clicking on the “+” to expand John Grimsley’s Case Study), the healthy person’s slide is white, John Grimsley’s slide is brown, and the boxer’s slide is close to black.

Trends in Biomedical Research: Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and the NFL

What’s more troubling about Dr. McKee’s studies is the relationship between CTE and the NFL. Former Tampa Bay Buccaneer and Philadelphia Eagles lineman Tom McHale was among the athletes whose brains she studied. McHale died in 2008 at the age of 45 from a drug overdose likely linked to the symptoms he suffered from CTE. In his journal, McHale wrote that he felt he was losing his mind and had become addicted to painkillers—changes that were said to be highly out of character. Dr. McKee said McHale’s brain showed “tremendous neurodegeneration.”

“What we have seen in all of these players… is a trauma-induced disease. It is caused by trauma. And so, I don’t think there is any question about what has caused the disease in these players,” Dr. McKee said in testimony about her research on CTE before the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary in October 2009. “None of my colleagues have ever seen a case of CTE without a history of head trauma.”

A survey by the Associated Press in November 2009 showed approximately 32 of the 160 NFL players surveyed—20 percent—replied that they have hidden or downplayed the effects of a concussion. Half said they have had at least 1 concussion, and 50 players—roughly 38 percent—missed playing time due to head injury. According to Pittsburgh Steelers linebacker James Farrior, “It’s just a natural reaction for you to fib a little bit and not give all the doctors all the information because you want to go out there and play. You don’t want them to come back and tell you you’re not able to play.” The common perception of concussions is similar to Atlanta Falcons center Todd McClure’s, “If you come out [of a game], you’re seen as ‘soft.’ That’s the way it is.”

While players may currently hide their concussions in order to play, they may not be able to hide from them in the future. In a 2009 study at the University of Michigan commissioned by the NFL, 6 percent of retired NFL players over the age of 50 had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, dementia, or another memory-related disease. This study shows the much higher level of diagnoses in NFL players than in American men of a similar age who did not play professional football. The incidence in these men is only 2 percent.

What Is Being Done, and Is It Enough?

In 2007, the NFL mandated neuropsychological baseline tests and retests for players before they can return to play after sustaining head trauma. The NFL now prohibits players from returning to a game from which they were knocked unconscious and also established a hotline to report pressure to play against a doctor’s advice. The hotline was created after New England Patriots coach Bill Belichick convinced former linebacker Ted Johnson to play too soon after a concussion, after which he sustained a more severe injury.

In 2015, the NFL released a new concussion poster to its players. It discloses more information about the effects of repeated head trauma than in previous information released to its players and, for the first time, acknowledges the serious long-term harm that concussions cause.

How Do We Protect Our Future Athletes?

It’s no secret that adolescents idolize athletes. They want to be like them and play the same sports. But how do we prevent them from making the same mistakes our current athletes make? How do we protect a generation of young athletes who still celebrate the current warrior mentality of the NFL?

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell has lobbied for states to adopt legislation similar to the Lystedt Law, which prevents a child from returning to play too soon after suspicion of a concussion and promotes concussion education and awareness. Concussions are not uncommon to football played at all levels. In fact, they can be even more devastating to someone whose brain is still developing, as injuries can take longer to heal. In 2006, Zackary Lystedt was 13 years old when he suffered permanent brain damage. He collapsed during a junior high football game from brain hemorrhaging after returning to play 60 seconds after sustaining severe head trauma. He remains in a wheelchair.

A major issue with concussions is they can be difficult to diagnose, and many student athletes return to play too soon. Many high schools lack the necessary medical personnel and equipment to examine athletes properly. A concussed athlete who returns to play before their brain is properly healed is more susceptible to sustaining an even worse injury known as second-impact syndrome—a condition in which the brain is vulnerable to another, often more severe, injury. Sixteen-year-old Jaquan Waller died during a game two days after sustaining brain trauma in practice. A medical examiner said “neither impact would have been sufficient to cause death in the absence of the other impact.” Waller was cleared to play by his team’s certified athletic trainer.

Making the proper diagnosis of a concussion and removing an athlete from play are hard enough when the symptoms are there. But the true danger lies in the inability to diagnose someone who demonstrates no symptoms.

A 2012 Purdue University study monitored 21 high school football players for an entire season. Four of the players were not diagnosed with concussion but suffered from brain injury equal to if not worse than players who were diagnosed with a concussion and removed from play. Researchers found these four undiagnosed athletes to have had a significant decrease in routine cognitive tests as well as decreased brain activity associated with memory. This was the case for Cincinnati Bengals’ wide receiver Chris Henry, who died in 2009 at the age of 26. An autopsy revealed that his brain had signs of degeneration—he had CTE. But the most troubling aspect of this finding is that Henry reportedly never sustained a concussion in his collegiate or professional football career. You do not have to have a history of concussions to develop CTE.

Henry’s case might seem shocking, but another common misconception is that an athlete must lose consciousness in order to sustain a concussion. In fact, it is not always the severity of the hit that can cause brain trauma leading to CTE. The mere accumulation of hits can be just as devastating.

Here are some figures to think about:

- a high school lineman receives between 1,500 and 1,800 subconcussive hits each season

- someone who plays four years of high school football can experience 6,000 to 7,200 subconcussive hits

- playing 4 years of college football additionally doubles the amount of hits—12,000 to 14,400 hits to the head before a player has the opportunity to play in the NFL

Not only does a player suffer from habitual head trauma while they play, but the longer they play and the further they advance in their career, the players around them get bigger, the speed of the game gets faster, and the hits get harder. This is why the NFL must consider these facts and figures before ever realistically proposing an expanded season.

High school athletes are taught to play through broken fingers and torn hip flexors; they are conditioned to play with pain. Why would a headache be a concern? The NFL needs to be proactive in changing the mentality of a game for an entire generation of young athletes. Over-competitive coaches must be taught not to force players onto the field prematurely. Parents and trainers must encourage kids to report their symptoms. Ultimately, athletes must be taught to care for themselves above playing a sport that lacks honest, responsible self-governance.

Review Questions

Here are some sample questions to review during this lesson:

- Which do we value more: watching sports, like football games, or the safety of athletes?

- Where is the technology to save the multi-million-dollar athlete?

- Should we reform the game of football? Can we?

- Is letting players play football any different than letting your friend drive drunk? Are fans the enablers?

- Is risk for serious injury part of what makes football, "football"? Propose a set of rules or policies that both protects players but also maintains the “essence” of football.

References and Further Reading

Bachynski K. No Games for Boys to Play: The History of Youth Football and the Origins of a Public Health Crisis. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press; 2019.

Kerr ZY … Zuckerman SL. Concussion incidence and trends in 20 high school sports. Pediatrics. 2019. DOI.

Halstead ME, Walter KD, and Moffatt K. Sports-related concussion in children and athletes. Pediatrics. 2018. DOI.

Sabatino MJ, Zynda AJ, and Miller S. Same-day return to play after pediatric athletes sustain concussions. Pediatrics. 2018. 141(1 Meeting Abstract):203.